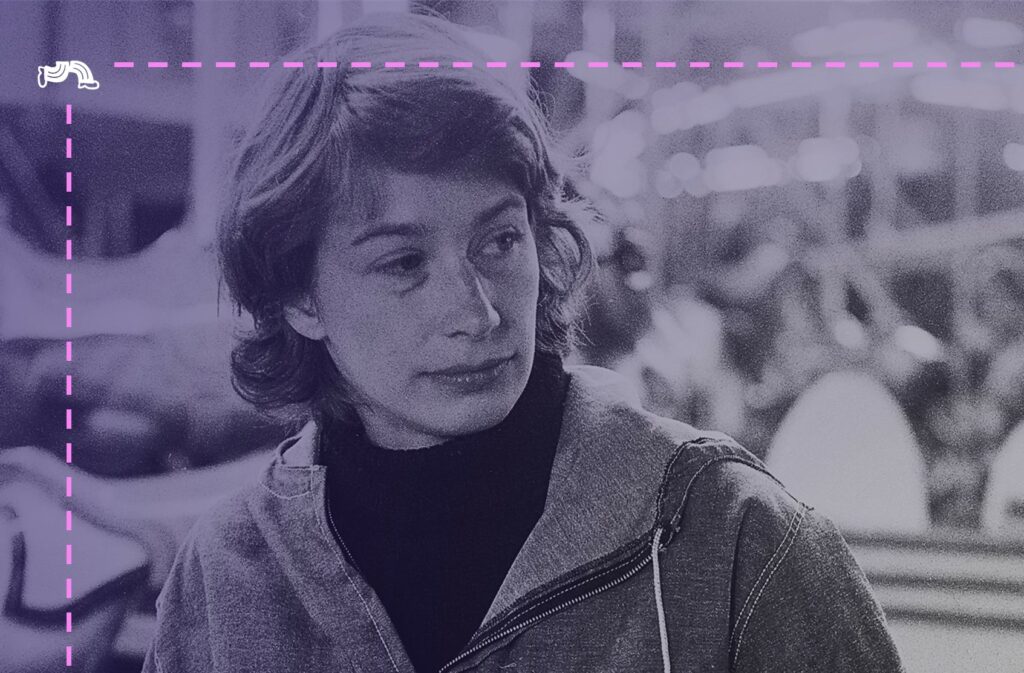

Who?

“I went from wanted criminal to best-selling writer.”

Benjamin Zephaniah left behind library shelves full of poetry, stories for all ages, plays, documentaries… even an album featuring The Wailers.

But when pressed to name his greatest achievement, he said reaching 30 “without being shot”.

By that age, he’d fallen in with a gang in Birmingham. He’d been through detention centres, borstal and prison. He’d seen three people die. And it put the fear in him.

“I remember lying in bed one night and I had a gun underneath my pillow and listening to a Marvin Gaye song and just thinking, ‘If I keep living like this I am going to die or I’m going to do a life sentence.’”

London, with its alternative “gang of poets and painters”, called to Zephaniah.

He’d always played with words: composing poems in his mind; rapping at church; toasting at concerts.

He published his first book, Pen Rhythm, in 1980. If we were speaking about another poet, that would be the moment we could sign off with “and the rest is history”.

Except that would imply Zephaniah’s life was in any way predictable. Or that he detached himself from his troubled youth – floating into the rarefied literary atmosphere of the capital.

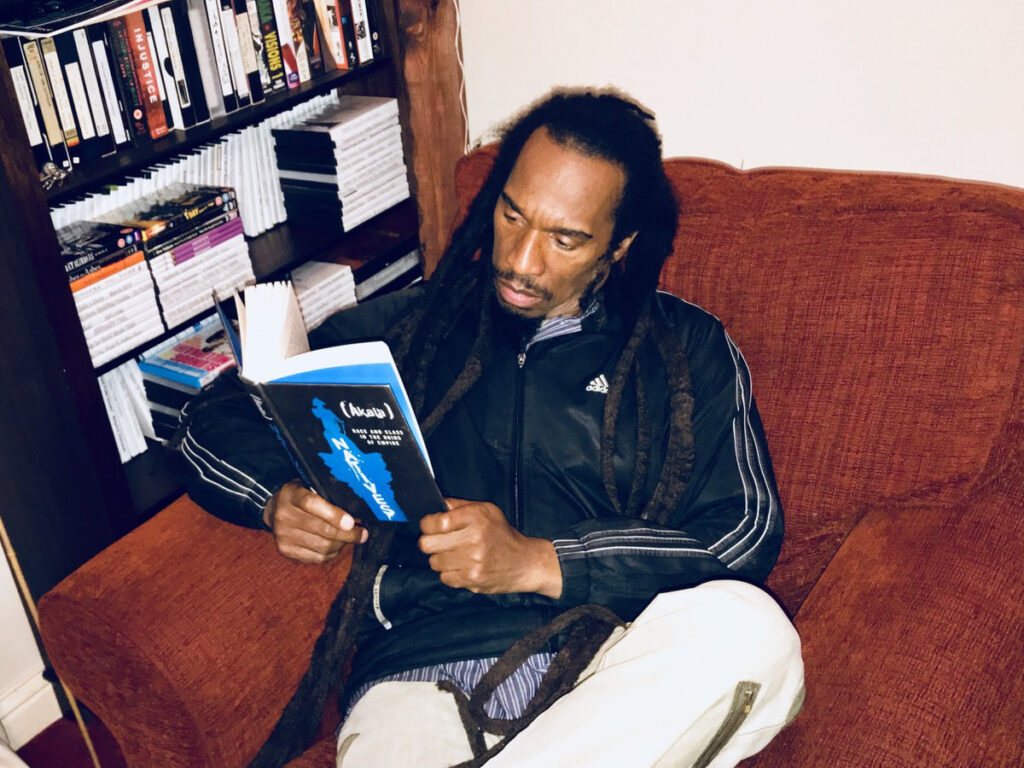

And we can’t do that. Benjamin Zephaniah lived many lives: poet, activist, actor, vegan, martial artist, Rastafarian. But he lived them all as himself. He was grounded.

What made him iconic?

In a piece about Zephaniah, Professor Kehinde Nkosi Andrews gave context for the poet’s boyhood:

“When Caribbean children first came to Britain in large numbers in the Sixties, they were deemed ‘education subnormal’, because of their ‘patois’ – which was seen as ‘broken English’.”

That explanation helped me understand why a psychiatrist saw Benjamin Zephaniah when the poet was seven.

The mental health professional told Mrs Zephaniah not to worry. Little Benjamin wasn’t sick. He was simply playing.

The proof was in the way he moved his lips: he mouthed along to lines that no one else could hear. Benjamin Zephaniah stared into space, “playing with words”.

Poetry was in him.

Dis poetry stays wid me when I run or walk

An when I am talking to meself in poetry I talk,

Dis poetry is wid me,

Below me an above,

Dis poetry’s from inside me

It goes to yu

WID LUV.

That’s from Dis Poetry – a manifesto piece for Zephaniah.

In the poem, Zephaniah gave Shakespeare his dues and admitted to trying Romance. But he rejected the heightened language of the sixteenth-century canon.

He wanted broad appeal:

Dis poetry is not afraid of going ina book

Still dis poetry need ears fe hear an eyes fe hav a look

Dis poetry is Verbal Riddim, no big words involved

An if I hav a problem de riddim gets it solved

He rhymed. He ranted. He raved. He refined a Verbal Riddim that could reach more people than sonnets.

And Zephaniah wasn’t on an ego trip. His work was done “fe the good of de Nation”.

By his account, it was his third visit to prison that made him political. And his politics matured and expanded with the decades.

Open his collected works and you’ll find poems about institutional racism (Too Black, Too Strong, 2001), Palestine (Rasta Time in Palestine, 1990) and animal rights (Talking Turkeys, 1994).

All in his signature style.

How does the work… work?

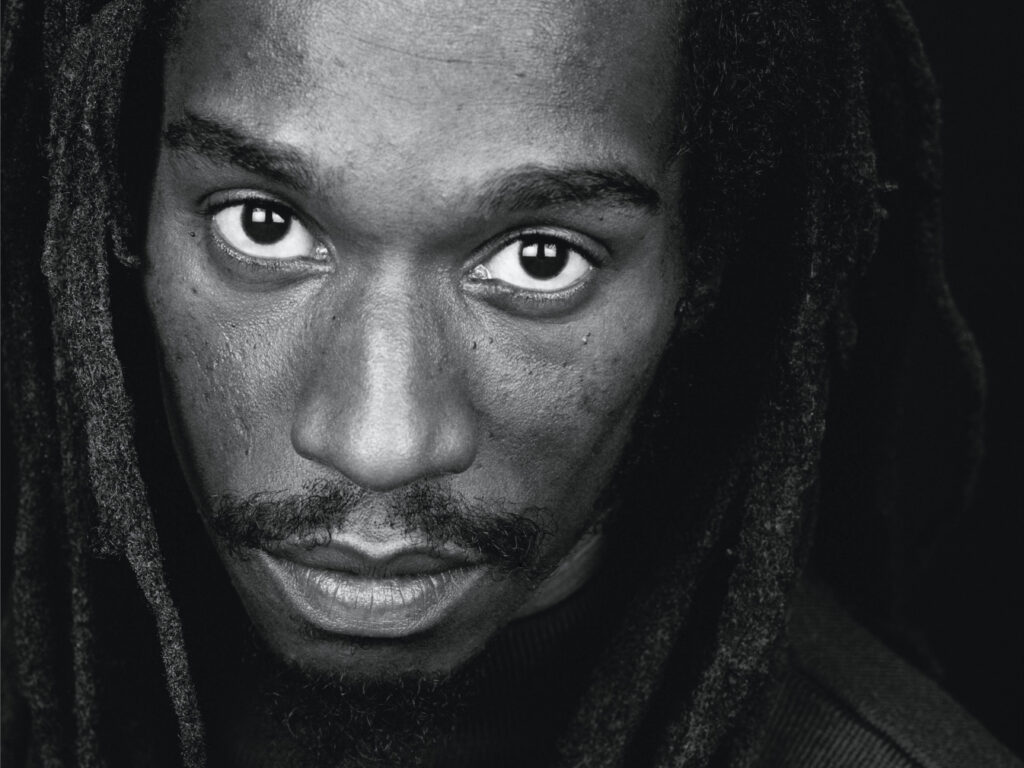

Zephaniah’s poems were political to the bone. They were spelt phonetically, in the voice of their author.

And that was daring. Zephaniah knew how Black language was feared and policed in Britain:

I am the type you are supposed to fear

Black and foreign

Big and dreadlocks

An uneducated grass eater.

I talk in tongues

I chant at night

But his style had deep roots. It took after dub poetry from Jamaica, where spoken-word artists were backed by reggae records.

Musicality was built into dub poems. Words were accentuated. Gestures were dramatic. The rhythm made hearts beat faster.

There was a connection between the performer and the audience. And Zephaniah just loved that.

“I realised I wanted to take my poetry onto television and perform in places where people never previously would perform – community centres, pool halls, barber shops. I wanted to take poetry to people.”

What’s the lesson, then?

I’m all for people writing more like they speak.

We’re all able to express our ideas in everyday conversation. So why wouldn’t we bring that ability to the screen and to the page?

It’s easy advice to give. But people find it hard to follow. A bizarre transformation occurs when they sit down and start typing – especially if they’re writing for work.

They turn into robots. Their natural expressions are replaced by cold, formal, “professional” language.

And why is that? Why do folk bring out technical talk and trendy boardroom jargon?

It’s an attempt to look intelligent.

But here’s the thing: those writers trying to be “professional” might be making the opposite impression.

Psychology professor Daniel Oppenheimer ran a relevant study at Princetown University.

He prepared two versions of an essay: one used complex language; the other was much simpler. Then, he had students read the essays and share opinions about the authors.

Here’s what Oppenheimer found:

“Anything that makes a text hard to read and understand, such as unnecessarily long words, will lower reader’s evaluations of the text and its author.”

Basically, the simpler and clearer your language, the smarter you seem.

I’d like to think that’s because readers can judge your ideas directly, without the distraction of thumbing through a dictionary.

And that should be a goal in any act of communication – even artistic ones. It’s part of the magic.

Like Zephaniah said:

“Poetry is simply taking everyday words that we use and arranging them in a way that touches people.”

Right. Any parting poetic thoughts?

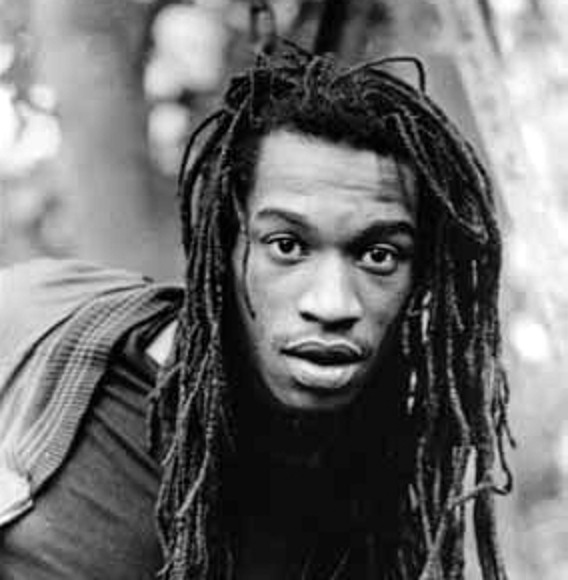

“My audience wasn’t even readers.”

Zephaniah was justifiably proud that his performance poetry reached people untouched by any other writer.

He reached them by speaking directly to them – both through the words he chose and because he stood up as a member of marginalised groups – groups who weren’t often invited onstage at Hay Festival.

His way of writing… his way of dressing… his way of wearing his hair… It sent a signal: Hey, it’s okay to be you.

Before I was a big poetry reader, I was open to his work. Because I knew we had one big thing in common: we were both dyslexic.

I held my head higher in class, because I had Zephaniah as a role model. I dared raise my hand.

And I didn’t let the embarrassment of misspelling stop me from writing. Zephaniah had his voice. So I’d use mine.

Thank you, Benji.

Aidan Clifford shares business lessons from creative icons. He writes for Pinstripe Poets – artists who love their day jobs.