Adapt like… who?

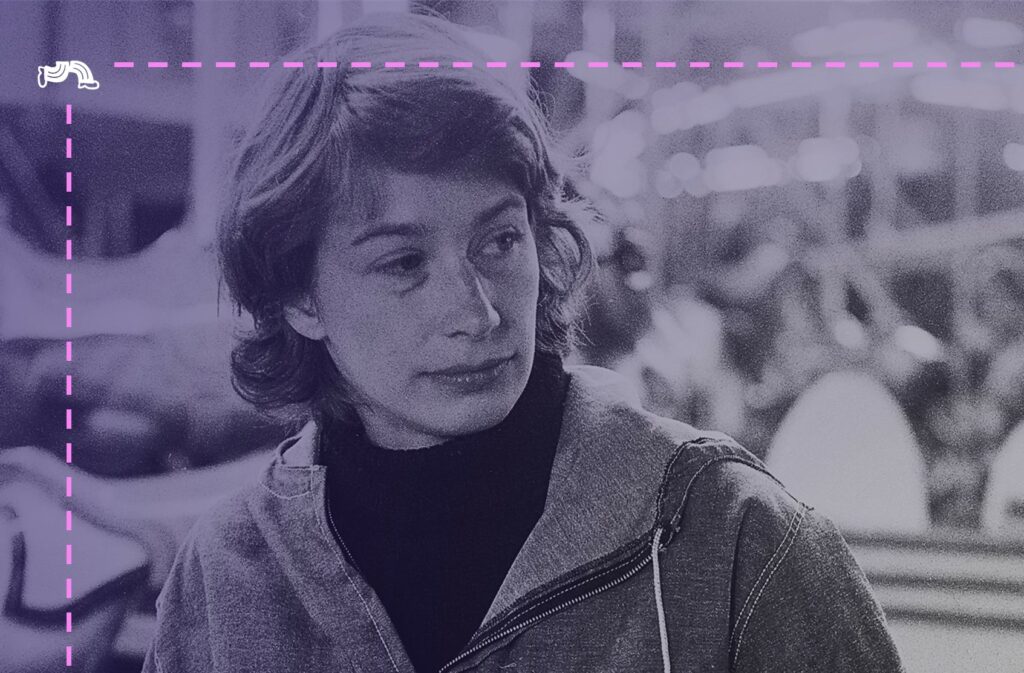

Garry Kasparov was a professional chess player. Now he’s an amateur, among other things.

You can tell his story by listing opponents: Anatoly Karpov in the eighties; Deep Blue in the nineties; Vladimir Putin in the noughties and through to today.

(And, yes, Vladimir Putin is that Vladimir Putin. The head of what Kasparov calls a “mafia state”. But, back to the timeline…)

He beat Karpov when he was just 22. The victory made Kasparov the youngest undisputed world champion chess had ever seen.

The rivalry between the players ran deep. They had a difference of philosophy that spanned chess (Karpov was a classical stylist; Kasparov was a young rebel) and entered politics.

The “two Ks” were Russians with opposing feelings for the Soviet Union. Reporting on their title match, The Guardian picked up on:

“… an undercurrent of tension between Karpov – darling of the Soviet establishment, personally decorated by President Brezhnev – and the ambitious youngster from provincial Baku.”

The state held no majesty for Kasparov. He’d peeked through the iron curtain, called to the West by international games.

“It was obvious to me very quickly that they were the free world and we were not, despite what Soviet propaganda told us.”

Once Kasparov claimed the number one spot, he held the rank until retirement. Opponents said he towered over the chessboard. The “Beast of Baku”.

But, even as Kasparov ascended to the highest heights, an American corporation was designing a player who could overpower his genius through brute, mechanical force.

What made him iconic?

In chess, nothing else mattered: 1997 was the year Garry Kasparov clashed with a computer.

Even people who didn’t know a rook from a pawn could see the significance of the match.

Newsweek called it “The Brain’s Last Stand”. IBM’s scientists called it a programming challenge:

“Chess requires all sorts of forms of intelligence, reasoning, careful planning through sequences, evaluation of consequences.

“If we could get computers to do all of that, then we presumed computers to be intelligent.”

There are sweat-drenched accounts of the match. Seek them out, if you’re interested in the drama. We can make do with a short version here.

Allow me three sentences:

- High in a Manhattan skyscraper, Kasparov played IBM’s Deep Blue.

- He was “the defender of humanity”; Deep Blue, a forefather of AI.

- Annnnnd… it didn’t go well for homo sapiens.

In the final game, Deep Blue boxed the grandmaster into a corner and Kasparov resigned – seething.

He was angry at himself for making a costly blunder and “losing to a $10 million alarm clock”. And he was angry at IBM, who he suspected of cheating.

But time smothered his rage, cleared his suspicions. And finally, Kasparov’s mind – trained to learn from every opponent – could get working.

“While licking my wounds, I got a lot of inspiration from my battles against Deep Blue.

“As the old Russian saying goes, if you can’t beat them, join them.”

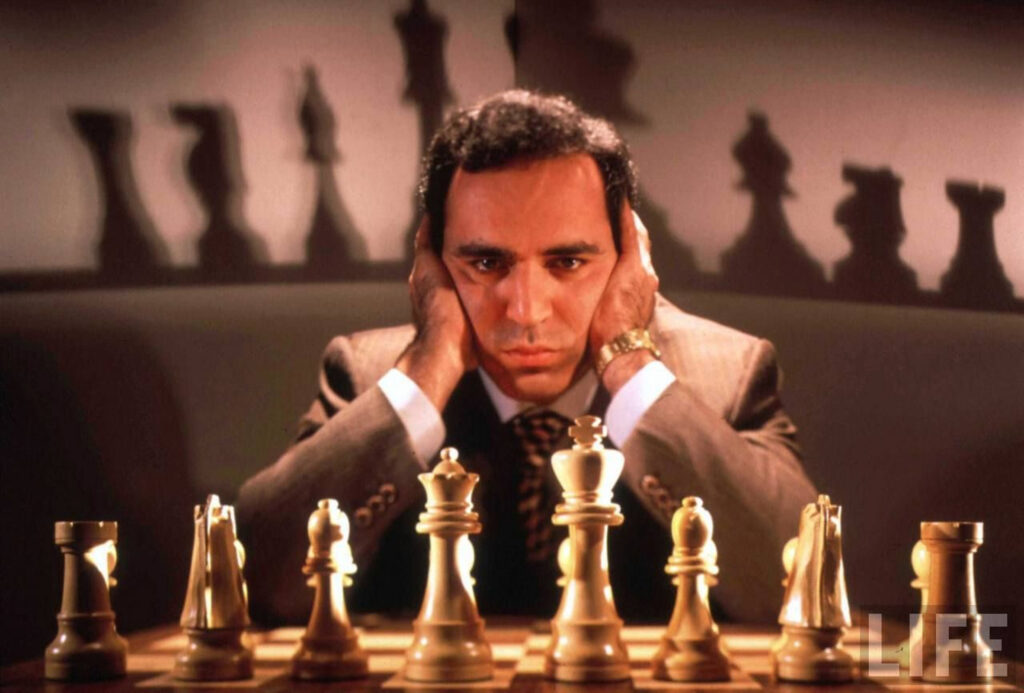

Kasparov eventually coined a law, based on his encounters with AI. We’d do well to learn it.

What’s the lesson, then?

Like the rest of the world, Kasparov’s preoccupation with AI has only intensified. And given the current giddy rush to adopt the tech, “Kasparov’s law” could be the buzz-phrase of the future – influential as “Parkinson’s law” or “the Peter principle”.

After the Deep Blue match, Kasparov invented “advanced chess” – a team sport where half of each team is robotic.

A human with a laptop plays another human with a laptop. Before they move pieces on the board, they simulate their options through chess software and observe the effects.

The results surprised even Kasparov: amateurs began beating grandmasters. And, when the rules were really loosened, whole tournaments went the same way.

In 2005, a website called playchess.com hosted a “freestyle” competition: people could team up with other players or computers.

The favourite to win was a grandmaster paired with a PC more powerful than several Deep Blues. But the eventual victors were two low-ranking Americans who bounced between three laptops. They were simply better at coordinating and coaching AI.

Episodes like that inspired “Kasparov’s Law”. As a formula, it looks like this:

(weak human + strong process + machine) > (strong human + inferior process + machine)

Which means that average minds can take on savants, if they play nicely with their machines. They can make more of their actual intelligence using artificial intelligence.

In chess – as in so many realms of life – the future lies in:

“finding ways to combine human and machine intelligences to reach new heights, and to do things neither could do alone.”

Right. Any parting poetic thoughts?

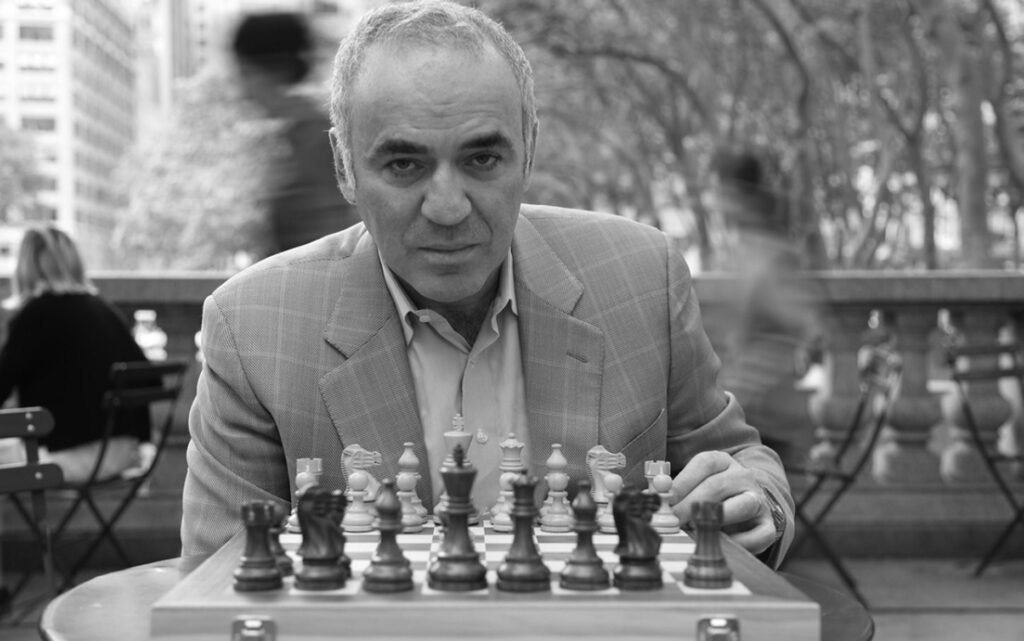

Time and again, Kasparov won because of the depth of his strategy. He knocked opponents off the board by playing a bigger game.

That’s part of his adaptability.

The real secret of it, actually.

He makes moves in the moment that take a while to make sense to anyone with less than a genius IQ.

“If you can recognize the strengths and weaknesses of your opponent, then you can start thinking about designing the game that will be beneficial for you …”

Chess gave him celebrity. Celebrity gave him influence. Influence gave him a means for opposing the Russian state.

That’s why Putin appears in Kasparov’s list of opponents. And we should mention this ongoing and bitter political game. Because it suggests AI could be a distraction.

Through his activism, Kasparov invites us to look at the true enemy of humanity. Itself.

“Humans still have the monopoly on evil. The problem is not AI. The problem is humans using new technologies to harm other humans.”

We’re playing against people far more terrifying than machines. In a match like that, you should use every advantage at your disposal.

So there’s a final, pessimistic argument for adapting to AI. Do your best to design the game that will be beneficial for you.

Aidan Clifford shares business lessons from creative icons. He writes for Pinstripe Poets – artists who love their day jobs.