Who?

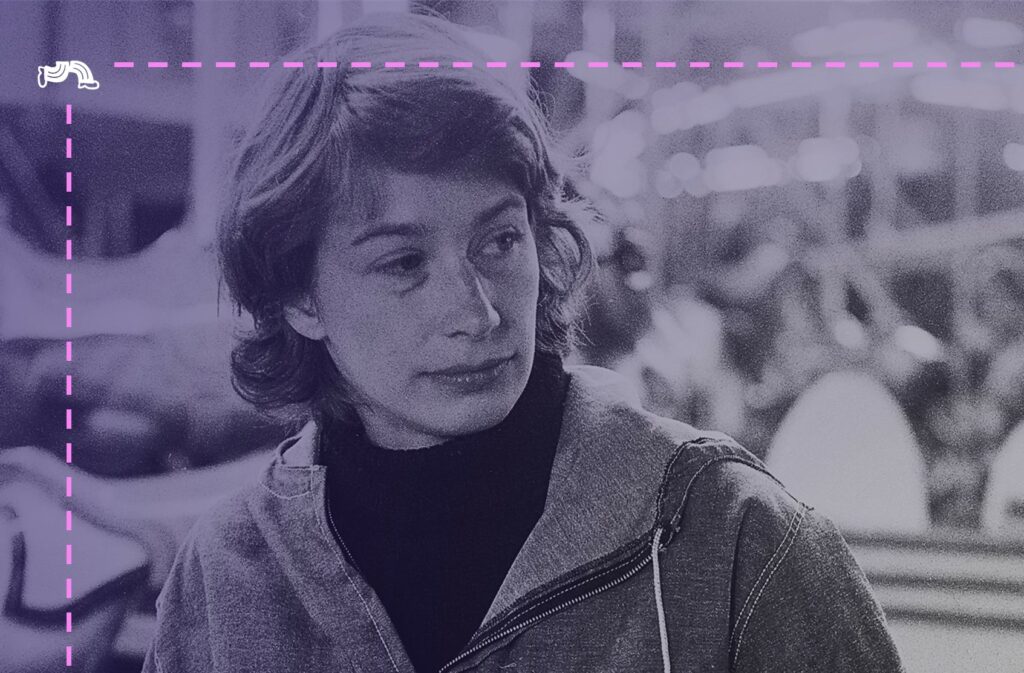

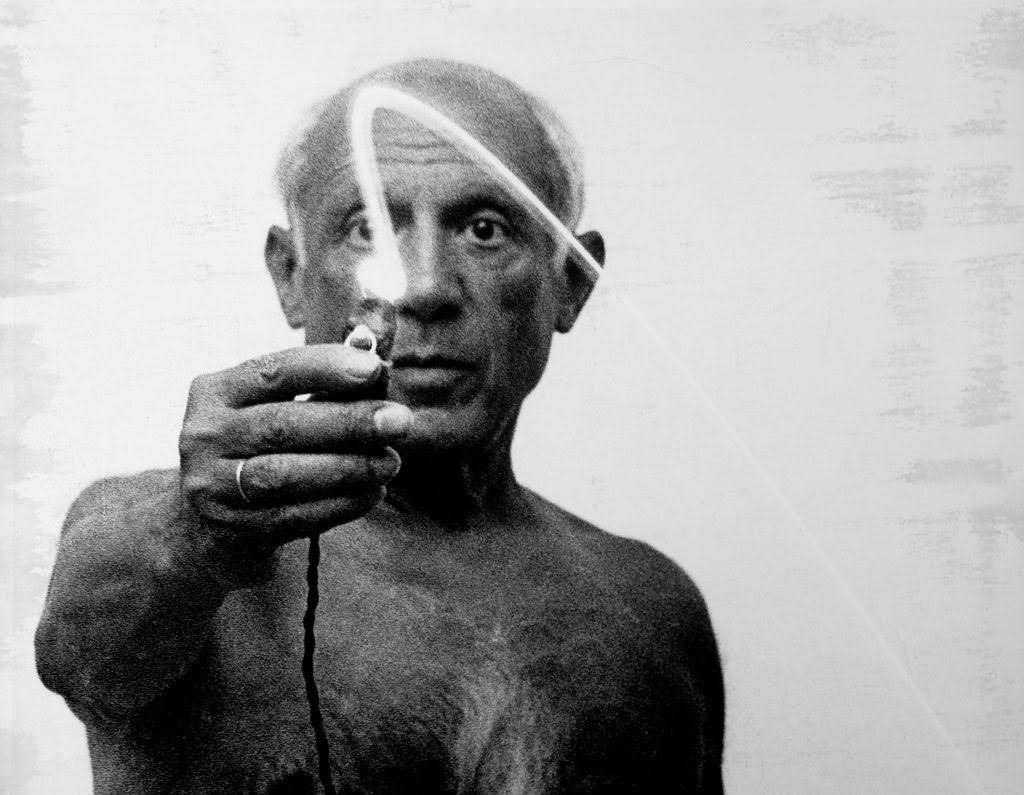

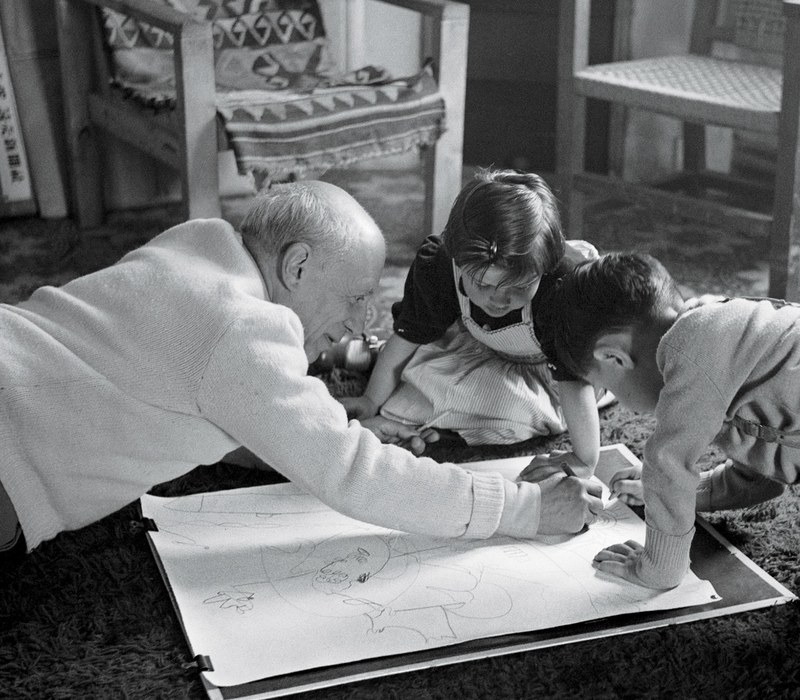

Damn. Pablo Picasso can still fix you with a stare.

Black and white photos preserve the mirada fuerte – the strong gaze. His eyes smoulder like cigarette burns.

Picasso’s daughter Angela Rosengart once recalled sitting for a portrait:

“He ate me with his eyes; you could feel him swallowing whatever he looked at.”

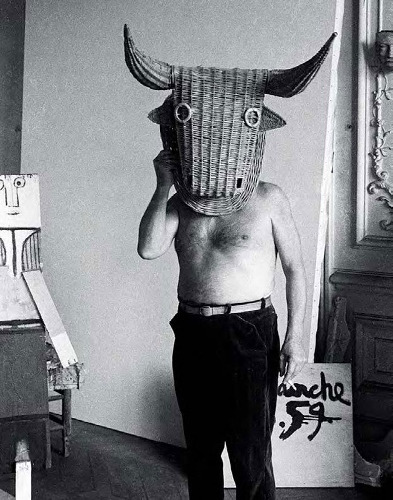

Bulls, horses and doves. Guitars and flowers. Men and women, women, women. All were lit by his vision.

They wilted, warped, bucked and bulged in the furnace of Picasso’s imagination – becoming the 26,000 pieces of art catalogued by researchers. Relics of a staggeringly productive life.

For Picasso’s younger daughter, Paloma Picasso, the subjects of these paintings and sculptures were willing victims:

“People were happy to be consumed by him. They thought it was a privilege. If you get too close to the Sun, it burns you. But the Sun can’t help being the Sun.”

What made him iconic?

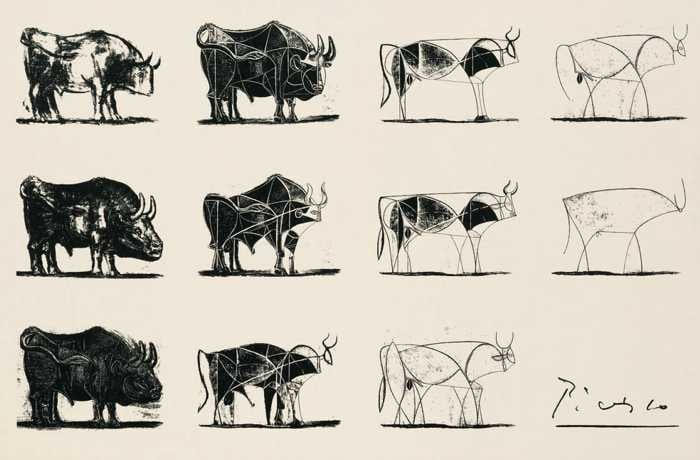

“I paint objects as I think them, not as I see them.”

So said Picasso.

As a young man, his thoughts were coloured by emotion: they were blue with grief; rose-tinted with cheer.

Then, his thoughts snagged on the central problem of painting: how to render three-dimensional objects on flat canvas.

Picasso’s solution was cubism. He mapped every surface, turned objects inside out.

To deepen his work, Picasso then sank into his subconscious, connecting his life with myth and Freudian symbolism.

That process took Picasso from painting like this in 1906:

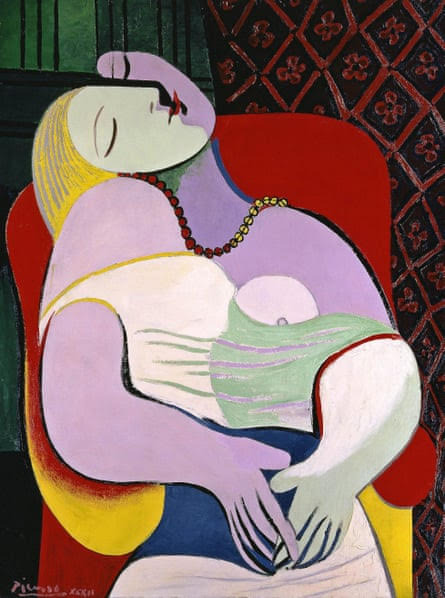

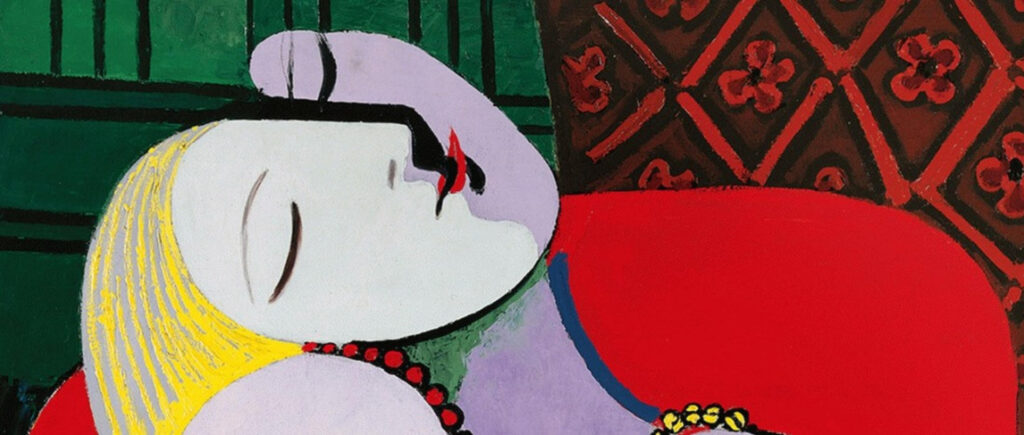

To painting like this in 1932:

And I want to linger on those two masterpieces. Because they reveal what it takes to produce like Picasso.

How does his work… work?

We have the timeline: Picasso went from Blue Period to Rose Period, from Cubism to Surrealism.

But I’ve made it sound like he was making discoveries alone, through introspection like a philosopher. Or through trial-and-error experimentation like a scientist in a lab. And that’s only part of the truth.

Biographer John Richardson provides the rest: Picasso was fuelled by people who influenced his mood, thoughts, and style.

“Picasso’s mistress from 1935 to 1944, Dora Maar, had a theory about the changes of the women in Picasso’s life. According to Dora, when the woman changed, everything else changed… the circle of friends, the house, the pets, the nature of his work changed. In Marie-Thérèse’s case, his work would become more overtly sexual.”

That last name belongs to the woman in the red armchair: Marie-Thérèse Walter.

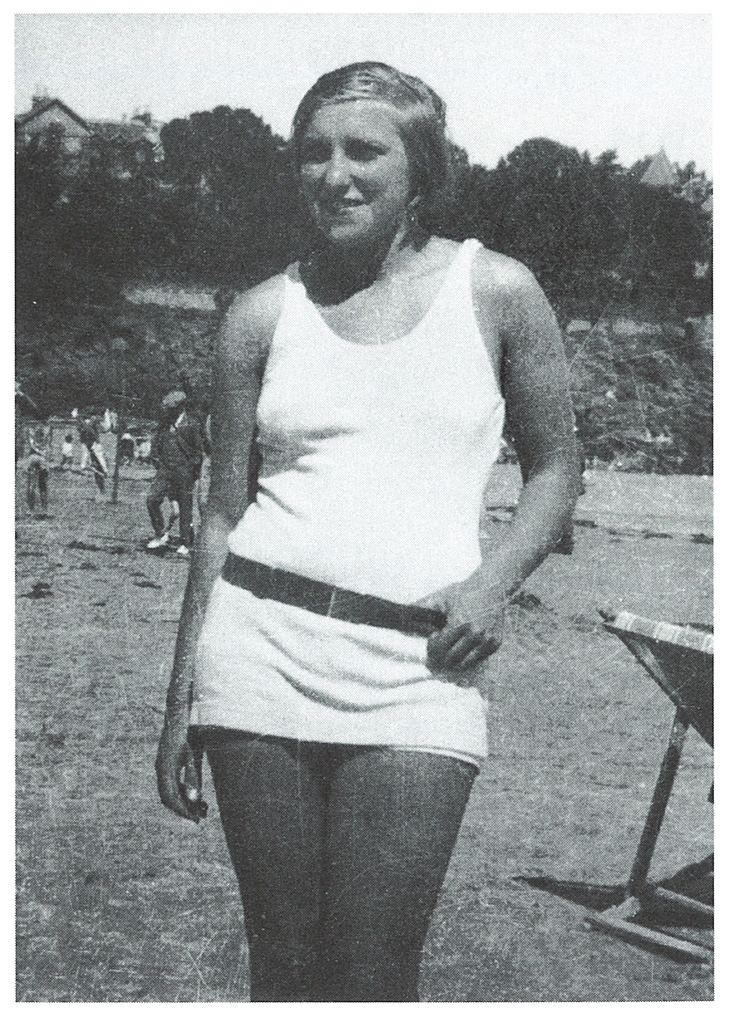

Photos show her as tanned and athletic, sand between her toes, blonde bob slick with seawater.

But that isn’t how art history sees Picasso’s “golden muse”.

Through 1932, as Picasso prepared for a major retrospective, he thought her into something new: an endlessly available lover.

Hundreds of images amassed during the summer. Walter slept, sprawled and dreamt in oils. And, then, in the autumn, she fell.

While kayaking, Walter toppled into the rat-infested water of the river Marne. She became gravely ill, lost her brilliant blonde hair, and saw less of Picasso.

Picasso, being Picasso, wrung inspiration from her crisis.

What’s the lesson, then?

There isn’t a noble lesson to draw from Picasso’s treatment of Walter.

Nor can we find anything to praise in the treatment of his wife, Olga Khokhlova. She had to view the byproducts of her husband’s affair at a crowded exhibition opening.

Picasso took far more than he gave in these relationships. Borrowing language from Wharton professor Adam Grant, we can call him a classic “taker”.

“Takers have a distinctive signature: they like to get more than they give. They tilt reciprocity in their own favour, putting their own interests ahead of others’ needs.”

Manage your relationships in that way and you’ll never be taken advantage of. But there’s a danger to being a taker.

Research shows that people tend to envy successful takers and look for ways to knock them down. Studying the performance of engineers and salespeople, Grant found “givers” win out in the end.

In 1935, Olga divorced Picasso and took custody of his son, leaving the artist bereft. A friend of Picasso recalls abandoned paintings. All his take-take-taking begins to look unsustainable, and not a little like self-sabotage.

“He no longer went upstairs to his studio. And the mere sight of his pictures and drawings infuriated him.”

Right. Any parting poetic thoughts?

By 1932, Picasso was world-famous. He was a chauffeur-driven celebrity, shopping for Normandy mansions. Perhaps we should have expected an ego.

Looking back to 1906, we spy a more sympathetic Pablo: someone who still had the capacity to give.

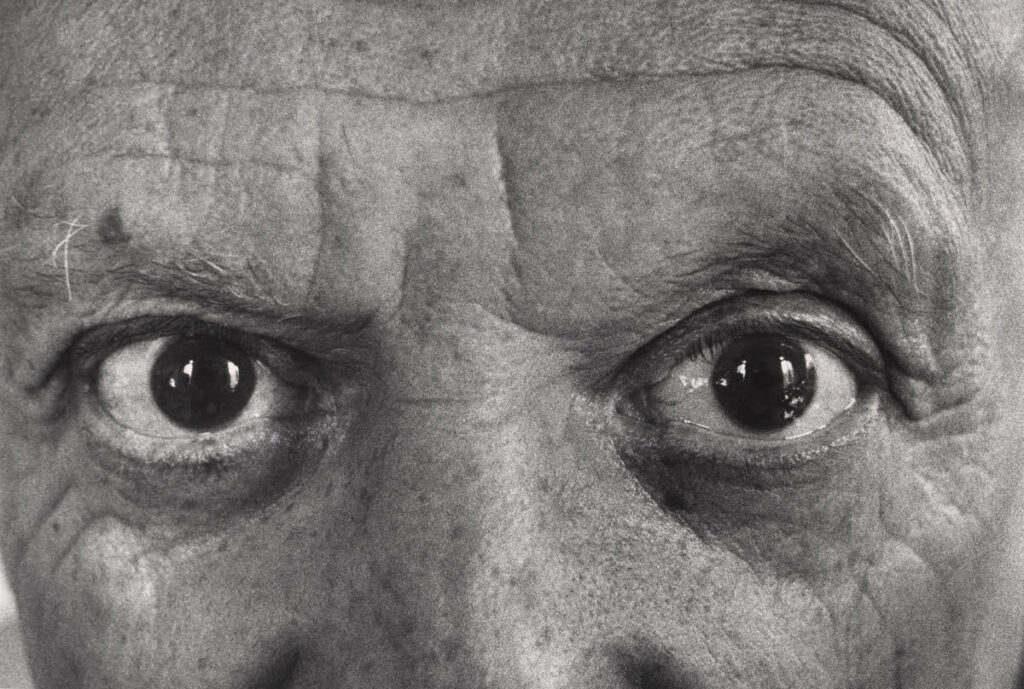

That was the year he finalised the breakthrough portrait of Gertrude Stein.

The painting was a frustrating, unrewarding labour for Picasso. Even after 80 or 90 sittings, he couldn’t properly render her head.

“I can’t see you any longer when I look.”

His struggle was understandable. Stein’s head was the seat of formidable forces of personality, intellect and creativity.

She was a writer who broke the rules of narration. Her language circled and turned. See this line from her poem about Picasso:

Shutters shut and shutters and so shutters shut and shutters and so and so shutters and so shutters shut and so shutters shut and shutters and so.

With her partner Alice Toklas, Stein was also the host of Paris’s leading salon. Hemmingway said it was “warm and comfortable and they gave you good things to eat and tea and natural distilled liqueurs”.

No wonder Picasso’s paints stuttered before her. Evading the problem, Picasso left for Spain, where he saw ancient Iberian sculptures.

The artefacts provided the visual language Picasso needed. In 1906, he confronted the gap in the picture and gave Stein a mask with penetrating eyes.

Some questioned the likeness. Stein was never in doubt: Picasso revealed her as she was.

“For me, it is I, and it is the only reproduction of me, which is always I.”

He didn’t use her as a prop, as he had Walter. No – in this earlier relationship, Picasso gave more than he needed to. He relearned his art to do justice to his friend.

Here is where we can finally learn something, because Picasso the giver was also successful. Stein and her family became his greatest collectors (until they were priced out of the market). They got him through a precarious stage of his career.

And there was something about their relationship that kept Picasso generous. At the height of his fame, when Stein could no longer afford his art, Picasso continued to gift her pieces.

So, that’s a measurable return on good behaviour. Other rewards are harder to express in numbers – but somehow seem even more profound.

While Picasso’s daughters remembered him as a blazing sun, Stein’s recollections have a gentler glow.

Read an extract from Stein’s book The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, in which Stein – ever subversive – refers to herself in the second person:

“I wish I could convey something of the simple affection and confidence with which he always pronounced her name, and with which she always said, ‘Pablo’. In all their long friendship with all its sometimes-troubled moments and its complications, this has never changed.”

I’d call that loving, challenging, and stimulating friendship one of Picasso’s greatest works.

And I’d apply those same three adjectives to the portrait of 1906.

Loving, challenging, and stimulating. The kind of success you only get if you give.

Aidan Clifford shares business lessons from creative icons. He writes for Pinstripe Poets – artists who love their day jobs.