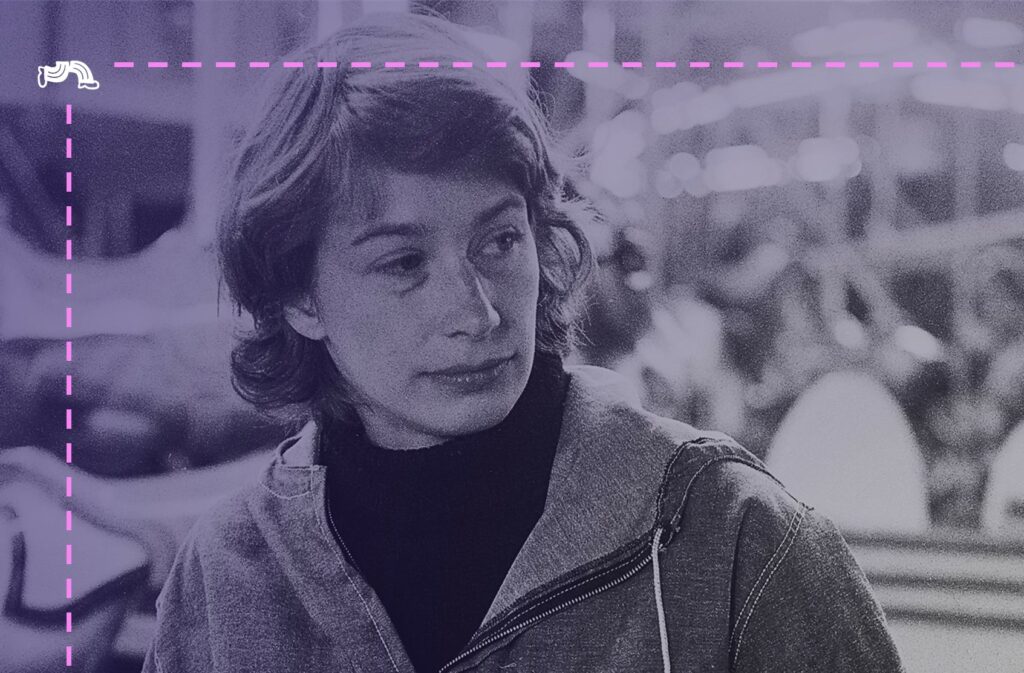

Don Norman was inspired by doors, computers and – finally – teapots

He was already a respected thinker when revelation struck.

He’d taught at university, worked at Apple, published a best-selling book. But there was more to learn. And three teapots held answers.

We’ll get back to Don, because I so admire his restless quest for knowledge. I wish I’d been so self-critical at the start of my career.

“Edit for emotion.”

That was the vital instruction I was missing. It took me years to make room for feelings on the page. And that period amounted to my reign of terror as an editor.

I’d pick up a colleague’s draft, click my tongue in consternation, and edit. And, when I say ‘edit’, I mean I’d hack the document to the bone.

Every word was on trial. Did it carry vital information? No. Would the reader get the gist without it? Yes. I’d snip it without a twinge of guilt.

Judge. Jury. Executioner.

I regret these excesses

I let messages stagger out into the world that were gaunt and joyless. Their meaning was clear, but their tone was terse or flat or staccato.

Where were the voluptuous descriptions? The personable asides? The slippery red herrings? Where (as the Black Eyed Peas almost sang) was the love?

Don could tell you

Don Norman wrote his first best-seller about how to design practical objects. But he realised he’d missed something huge – and he followed with a book called Emotional Design.

You see, when you pick up your favourite objects, you have three responses:

- A visceral response (the attraction of handling something beautiful)

- A behavioural response (the satisfaction of using something practical)

- A reflective response (the importance of owning something meaningful)

You can pack a whole lotta feeling between handle and spout

Emotional Design introduces the three responses by describing Don’s bizarre collection of teapots:

“One of them is completely unusable – the handle is on the same side as the spout. It was invented by the French artist Jacques Carelman, who called it a coffeepot: a ‘coffeepot for masochists’.”

You can’t tip this pot without scalding yourself. But Don prized it as an art object. That means it had reflective value.

“The second item in my collection is the teapot called Nanna, whose unique squat and chubby nature is surprisingly appealing.”

Now, that’s a charming object. It works viscerally.

“The third is a complicated but practical ’tilting’ pot made by the German firm Ronnefeldt.”

Don said it himself. The design is practical.

What does all this have to do with words?

When I edited messages to within an inch of their lives, I made them entirely practical. I gave readers all the information they needed to take their next action. Nothing more. In Don Norman’s terms, I was writing for a behavioural response.

Writers can do so much more

We can attract with beautiful, generous, sensory language.

We can stir with stories that tell readers something about themselves.

We can weigh words like Don Norman reviews teapots – with an eye for aesthetics and meaning, as well as usability.